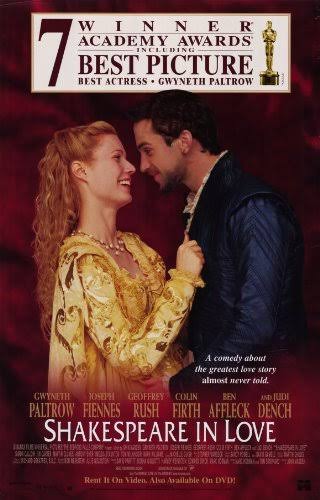

Shakespeare In Love Movie Review; Is this a movie or anthology?

There is a boatman in “Shakespeare in Love” who ferries Shakespeare across the Thames while bragging, “I had Christopher Marlowe in my boat once.” As Shakespeare steps ashore, the boatman tries to give him a script to read. The contemporary feel of the humor (like Shakespeare’s coffee mug, inscribed “Souvenir of Stratford-Upon-Avon”) makes the movie play like a contest between “Masterpiece Theatre” and Mel Brooks. Then the movie stirs in a sweet love story, juicy court intrigue, backstage politics and some lovely moments from “Romeo and Juliet” (Shakespeare’s working title: “Romeo and Ethel, the Pirate’s Daughter”).

Is this a movie or an anthology? I didn’t care. I was carried along by the wit, the energy and a surprising sweetness. The movie serves as a reminder that Will Shakespeare was once a young playwright on the make, that theater in all times is as much business as show, and that “Romeo and Juliet” must have been written by a man in intimate communication with his libido. The screenplay is by Marc Norman and Tom Stoppard, whose play “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead” approached “Hamlet” from the points of view of two minor characters.

“Shakespeare in Love” is set in late Elizabethan England (the queen, played as a young woman by Cate Blanchett in “Elizabeth,” is played as an old one here by Judi Dench). Theater in London is booming–when the theaters aren’t closed, that is, by plague warnings or bad debts. Shakespeare (Joseph Fiennes) is not as successful as the popular Marlowe (Rupert Everett), but he’s a rising star, in demand by the impecunious impresario Henslowe (Geoffrey Rush), whose Rose Theater is in hock to a money lender, and Richard Burbage (Martin Clunes), whose Curtain Theater has Marlowe and would like to sign Shakespeare.

The film’s opening scenes provide a cheerful survey of the business of theater–the buildings, the budgets, the script deadlines, the casting process. Shakespeare, meanwhile, struggles against deadlines and complains in therapy that his quill has broken (his therapist raises a Freudian eyebrow). What does it take to renew his energy? A sight of the beautiful Viola De Lesseps (Gwyneth Paltrow), a rich man’s daughter with the taste to prefer Shakespeare to Marlowe, and the daring to put on men’s clothes and audition for a role in Will’s new play.

Players in drag were of course standard on the Elizabethan stage (“Stage love will never be true love,” the dialogue complains, “while the law of the land has our beauties played by pipsqueak boys”). It was conventional not to notice the gender disguises, and “Shakespeare in Love” asks us to grant the same leeway, as Viola first plays a woman auditioning to play a man and later plays a man playing a woman. As the young man auditioning to play Romeo, Viola wears a mustache and trousers and yet somehow inspires stirrings in Will’s breeches; later, at a dance, he sees her as a woman and falls instantly in love.

Alas, Viola is to be married in two weeks to the odious Lord Wessex (Colin Firth), who will trade his title for her father’s cash. Shakespeare nevertheless presses his case, in what turns out to be a real-life rehearsal for Romeo and Juliet’s balcony scene, and when it is discovered that he violated Viola’s bedchamber, he thinks fast and identifies himself as Marlowe. (This suggests an explanation for Marlowe’s mysterious stabbing death at Deptford.) The threads of the story come together nicely on Viola’s wedding day, which ends with her stepping into a role she could not possibly have foreseen.

The film has been directed by John Madden, who made “Mrs. Brown” (1997) about the affection between Queen Victoria and her horse trainer. Here again he finds a romance that leaps across barriers of wealth, titles and class. The story is ingeniously Shakespearean in its dimensions, including high and low comedy, coincidences, masquerades, jokes about itself, topical references and entrances with screwball timing. At the same time we get a good sense of how the audience was deployed in the theaters, where they stood or sat and what their view was like–and also information about costuming, props and stagecraft.

But all of that is handled lightly, as background, while intrigues fill the foreground, and the love story between Shakespeare and Viola slyly takes form. By the closing scene, where Viola breaks the law against women on the stage, we’re surprised how much of Shakespeare’s original power still resides in lines that now have two or even three additional meanings. There’s a quiet realism in the development of the romance, which grows in the shadow of Viola’s approaching nuptials: “This is not life, Will,” she tells him. “It is a stolen season.” And Judi Dench has a wicked scene as Elizabeth, informing Wessex of his bride-to-be, “You’re a lordly fool; she’s been plucked since I saw her last, and not by you. It takes a woman to know it.” Fiennes and Paltrow make a fine romantic couple, high-spirited and fine-featured, and Ben Affleck prances through the center of the film as Ned Alleyn, the cocky actor. I also enjoyed the seasoned Shakespeareans who swelled the progress of a scene or two: Simon Callow as the Master of the Revels; Tom Wilkinson as Fennyman, the usurer; Imelda Staunton as Viola’s nurse; Antony Sher as Dr. Moth, the therapist.

A movie like this is a reminder of the long thread that connects Shakespeare to the kids opening tonight in a storefront on Lincoln Avenue: You get a theater, you learn the lines, you strut your stuff, you hope there’s an audience, you fall in love with another member of the cast, and if sooner or later your revels must be ended, well, at least you reveled.